Discussions on the stability of long-standing proportionate quota shares are ones we take extremely seriously. Ad hoc decisions to destabilize those shares would have long-lasting impacts on people, communities and the future of the fishery in Newfoundland and Labrador, and Canada. We believe those discussions and debates need to be grounded in factual information and a genuine desire to make the fishery better for people and communities in the long-term. With that in mind, we are compelled to correct some of the misinformation that has been shared by the FFAW Executive on Unit 1 redfish.

Basic Facts

| The FFAW Executive refers to Unit 1 redfish as a “new redfish fishery”. | |

| The Gulf redfish fishery was developed by offshore harvesters beginning in the 1950s and reaching over 50,000t through the 1960s to the early 1990s. This catch history is recognized as sector percentage shares by the Atlantic Sharing Arrangements – as is the catch history of all sectors for many stocks in Atlantic Canada.

The quota allocations for the subsequent 2,000 mt index fishery for this stock has been distributed consistent with these shares for over two-decades – including in 2021. While harvesting Unit 1 Redfish at low levels and waiting for the biomass to recover, Canada’s offshore harvesters have also continued to prepare for its future re-opening, recently investing nearly $100M in vessels, plants and advanced technology to harvest and process redfish. The Atlantic Groundfish Council has also been working towards expanding markets for Unit 1 Redfish with a $4.5M marketing campaign to develop markets in Asia and Europe in particular. |

|

| The FFAW Executive asserts the largest stock of Unit 1 redfish is in “4R”. | |

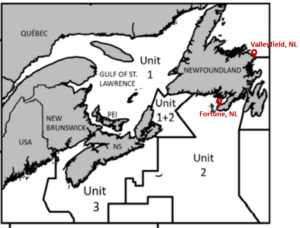

| This statement is incorrect. The Unit 1 Redfish stock is a part of the Gulf of St. Lawrence redfish complex that includes redfish all the way out through the Cabot Strait (between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland). There is no 4R stock, just as there is no 4S or 4T stock – they are the same fish from the same stock. There will be a single Total Allowable Catch for this entire stock complex. |

Adjacency

| The FFAW Executive argues that ‘adjacency’ is the basis for fish stocks to be allocated and presents this argument as a reason to take quota from offshore harvesters and give it to inshore harvesters. | |

Local offshore harvesters, their facilities are their employees are adjacent to Unit 1 redfish.

Offshore harvesters are Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. Ironically, most are dues-paying members to the FFAW. They live adjacent to the resource and deserve to make a living as much as anyone else. Plant workers at the plant in Fortune, NL, are also adjacent. The plant processes redfish from offshore quota. They are certainly more adjacent to Unit 1 than the plant in Valleyfield, NL that the FFAW Executive used as an example of a local plant that should be able to process redfish in its October 14, 2021 press conference. If the FFAW Executive argues for ‘adjacency’ to be the basis to be used for quota allocations, why do they agree with west coast NF inshore shrimp trawlers accessing shrimp quotas on the northeast coast of NF; why do they deny ‘adjacent’ offshore harvesters on the south and northeast coast of NL the right to harvest their traditional cod quotas in those areas? The inconsistency of their position is blatant; they use whatever argument is convenient to promote their own interests, even at the expense of their union members who work on offshore vessels. More broadly, Unit 1 redfish is surrounded by 5 Canadian provinces, all of which are ‘adjacent’ to this stock. How does one define who is ‘more’ adjacent than another? If catch history is not important to define quota shares of Unit 1 Redfish, then should other provinces ignore catch history for other stocks where NL’s share is the highest? This is a no-win issue that creates divisions within industry and precludes collaborative and cooperative approaches to increasing value in the seafood sector. |

|

| The FFAW Executive states that adjacency is foundational to the success of the Blue Economy. | |

| The Blue Economy is about resilient coastal communities based on sustainable utilization of marine resources, which is more likely to be achieved with good paying, year-round employment that attracts and retains investment, skilled labour and our youth. |

Markets

| The FFAW Executive claims there is high demand in US and EU markets for redfish. | |

| Redfish is not a high demand species in the US – redfish sales are currently significant in only two regional markets. Imports are now $4.5 million annually and have been shrinking at rate of about 8.5% per year. These markets are highly sensitive to price and volume and are a shadow of their former selves, with most of the former demand being taken over by farmed species, mostly at cheaper prices.

The EU market for redfish fillets is mature, with growth primarily in whole fresh redfish. EU markets are highly selective of the products that they consume, with uptake determined by product size, quality and sustainability. Current size profile of U1 redfish, produces fillets that are 1/5th of the size that EU consumers are willing to purchase. The opportunity to create new demand/consumption for redfish, mostly in China, is primarily for whole redfish – the product form that 90% of their consumers prefer for all fin fish. |

Value of Offshore Fishery

| The FFAW Executive falsely claims if the offshore receives its historical share (75%) redfish will be shipped to a low-wage country for processing, not landed fresh to communities along the Gulf of St Lawrence. | |

| The employees working on most NL offshore vessels are not only Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, they are members of the FFAW union. They harvest and process fish at sea, some of which will be further processed in shore-based plants in NL. Some will also be sold as “whole” or “head-off gutted” (H&G) fish, which is what most customers in Asia prefer.

The practice of producing whole or semi-processed fish to meet demands of customers in Asia is common in other fisheries where products are produced to meet the desires of consumers. For instance: · Greenland halibut caught by both inshore and offshore vessels are routinely shipped to markets in the EU and Asia in a frozen head-off and gutted (H&G) form because those premium markets do not normally consume the species as fillets. · Atlantic Halibut is routinely sold to markets in a fresh head-off and gutted form because full fillets are not used by customers, i.e., specific size portions are customized by local restaurants and retailers. · Snow crab consumers prefer to buy crab sections and whole crab, rather than meat being extracted in NL plants. Optimizing market value requires a mixed basket of product types balanced by consumer demand. |

|

| The FFAW Executive claims that an offshore dominated redfish fishery will provide little economic benefit to NL. | |

| The offshore fishery provides year-round, at-sea employment in harvesting and processing fish jobs, including redfish. Freezing-at-sea vessels, each provide 50-70 well-paying, year-round processing jobs; 10-14 times the crew of an inshore trawler, and virtually the same number as an average seasonal, land-based redfish processing plant. Employees on those vessels are from the rural areas of Newfoundland and Labrador, providing good paying jobs in regions in need of meaningful employment opportunities. These employees and their families are helping to maintain the viability of their rural communities.

Additionally, offshore fish is also processed in plants in several communities throughout the province. In fact, these plants that process a mixture of inshore and offshore products provide considerably more weeks of annual employment (i.e., 35, 40, 50 weeks) than seasonal plants. Finally, shore-based processing plants that are supplied by offshore harvesters operate during periods when inshore vessels cannot safely operate. The future of this fishery is not an ‘either one fleet or the other’, but a mix of inshore and offshore operations that can work together to advance the local economies of the province. |

|

| The FFAW Executive states that the offshore sector in the 70s and 80s was fundamentally different than it is today, suggesting this is a reason not to continue providing proportionate quota shares of redfish. | |

| The environment of commercial fisheries, including ocean ecosystems and sustainability demands from global customers, including desired product forms, is fundamentally different today compared to 50+ years ago.

50 years ago, sustainability was not even considered when a consumer chose their seafood – now it is a key component required for market access. 50 years ago, the processing industry focused on producing fillet blocks to service high commodity markets (e.g., fish sticks) – today this market represents a smaller component of production because of the relatively poor value it offers both harvesters and processors. The FFAW understands this evolution when it is in their interest to do so (e.g., with the export of whole or semi-processed crab or whole or semi-processed turbot (Greenland Halibut) to Asia in order to achieve better prices to inshore harvesters). |

Economic opportunity for inshore harvesters

| The FFAW Executive appears to be asserting that redfish will be needed by, and prove to be an economic generator for, inshore shrimp harvesters on the west coast of Newfoundland. | |

In most of the past several years, Gulf shrimp landed by the 40 NL inshore shrimp trawlers (~160 crew) has achieved the highest landed value of the last 30 years. When this fact is combined with the average price of shrimp being up to 5 times higher than redfish, it is not readily apparent that most of NL inshore shrimp trawlers will even want to harvest redfish on a regular basis. Redfish cannot be viably caught with gillnet or hook and line.  |

|

| The FFAW Executive claims that a “significant” portion of Unit 1 redfish being landed and processed in NL would support 1,000+ harvester and plant worker jobs, creating millions of dollars in annual economic development. | |

| Beyond the fact that global markets cannot absorb future production of the Unit 1 Redfish fishery if even half of it was produced into fillets, the processing capacity and labor shortages facing the processing sector today preclude the ability to put in place 1,000+ local harvester and plant workers jobs.

The statement belies the reality of redfish markets and the infrastructure and labour supply that is necessary to accomplish such a ‘goal’. Where is the analysis to support these claims? |

|

| The FFAW Executive is implying that taking quota from offshore sector and reallocating to the inshore will result in a net benefit for Newfoundland and Labrador. | |

| All 5 provinces around the Gulf of St. Lawrence have been participants in the Unit 1 redfish fishery, and it should be highlighted that this inshore redfish fishery is fished competitively by inshore trawlers from all of these provinces. |